General trading companies are shifting from an agency business model to one that generates profits commensurate with added value across the entire supply chain, from upstream to downstream. By devising logistics strategies aimed at optimizing the entire supply chain, they contribute to consumer benefits in the form of time savings and price reductions through economies of scale. Production Control System in Indonesia It’s not limited to Indonesia, but it’s often said that the ultimate goals of the manufacturing industry are twofold: "cost reduction through productivity improvement" and "delivering products on time without delays." From a management perspective, business plans are crafted to maximize growth based on market supply and demand adjustments. However, even if sales increase due to low pricing, it only reduces gross profit, leading to losses from selling and administrative expenses or non-operating costs. On the other hand, raising unit prices isn’t straightforward due to market price considerations. Therefore, process management based on production plans aimed at reducing costs through ... 続きを見る

Evolution of General Trading Companies’ Functions Due to the Spread of the Internet

I came to Indonesia in October 1997, and back then, Indonesians often said two things to me: "Lend me money" and "Let’s do business together." One major reason I’ve rarely heard these phrases recently is that Indonesians’ incomes have risen, making them more affluent. Another reason is the spread of the internet, which has enabled individuals and small businesses without connections to establish distribution channels to reach end consumers directly.

On the flip side, this could also mean that expectations toward Japanese people have diminished. With Indonesia’s demographic bonus (where the working-age population aged 15–64 is at least double the dependent population aged 0–14 and 65+) projected to continue until 2040, and its nominal GDP expected to surpass Japan’s by 2030, the position of Japanese people in Indonesia has shifted from "useful foreigners with money and connections" to "business rivals."

I still vividly remember that around the year 2000, as personal online shops sprang up one after another during the transition from the dawn to the growth phase of the internet, two major predictions about the upcoming business revolution were loudly proclaimed:

- An era will come where individuals can compete with large corporations on equal footing online.

- The role of intermediaries like trading companies and wholesalers will end as producers transact directly with consumers.

Looking at the situation in 2020, 20 years later, direct sales of houseplants or arowana fry from rural Java or near the jungles of Kalimantan are now possible via Tokopedia or Instagram. The decline of small trading companies and wholesalers that merely added intermediate margins in the supply chain suggests these predictions were largely accurate.

However, one clear miss is that the presence of Japanese general trading companies has grown stronger, consistently ranking high on students’ lists of preferred employers.

Despite events like Marubeni Corporation recording a record-high consolidated loss of 197.4 billion yen in March 2020 due to impairment losses (special losses recorded when the recoverable amount of assets like land, buildings, patents, or goodwill falls below book value) amid the COVID-19 pandemic, or Itochu Corporation surpassing Mitsubishi Corporation in market capitalization in June, the five major trading companies still hold significant relevance. This is evident in their roles in capital participation during the establishment of local subsidiaries of Japanese companies in Indonesia and in mediating material procurement (my wife worked at Itochu Indonesia handling cardboard procurement for manufacturers).

In my middle school politics and economics classes, the image of general trading companies was defined by their wide range of handled goods—"from ramen to missiles." Subsequently, they transitioned to a business model focused on earning profits commensurate with added value across the entire supply chain, from upstream (raw materials) to downstream (products).

Moreover, in February 2019, Mitsubishi Corporation’s multibillion-yen investment in GoJek made headlines. Rather than aiming for exits through sales or IPOs, they now fulfill an incubation function, emphasizing business continuity while coordinating with group companies.

- From handling a wide range of goods to a "general store" procurement and sales function

- A logistics function coordinating the supply chain from downstream to upstream

- A financial and nurturing function through investment and capital participation in business development

The spread of the internet has leveled the competitive environment for businesses in some respects. When procurement and production of goods are completed within a specific entity or region, direct producer-to-consumer businesses become viable. However, general trading companies, leveraging their group networks and financial strength to achieve "economies of scale," have redefined their core business as the organizer function of the entire supply chain, further enhancing their significance.

Decoupling Points in the Supply Chain

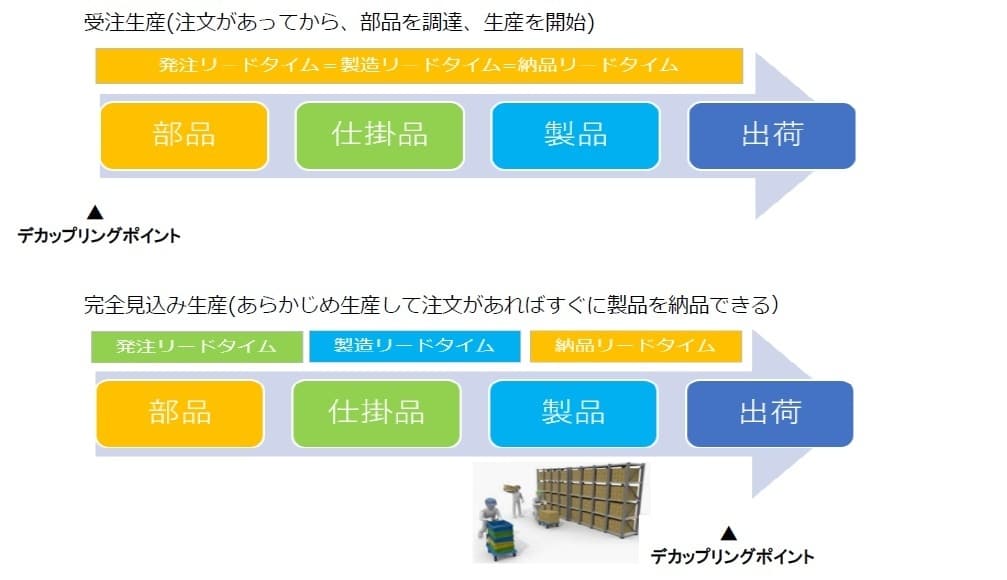

Manufacturing production forms are broadly classified into make-to-stock (MTS) and make-to-order (MTO). Dell Computer’s assemble-to-order (ATO) model, dubbed the "Dell Model," increased sales by holding semi-finished inventory and assembling products upon receiving customer orders. In the supply chain, an appropriate inventory level—neither too much nor too little—is required from order receipt to shipment.

Decoupling Points in the Factory

There are two reasons inventory is needed within a factory, and the same applies when viewing the entire supply chain. The ultimate "optimal" state is one where inventory replenishment and shipment occur simultaneously.

- Insurance to bridge the gap between manufacturing (supply) lead time and order (demand) lead time

- To prevent stopping the flow of the bottleneck process (main driver) that determines the factory’s overall productivity (supply capacity)

Locations holding inventory in the supply chain are called decoupling points. For make-to-order, where production starts after receiving orders and procuring raw materials, the "procurement point" applies. For make-to-stock, where goods are produced in advance and shipped immediately upon order receipt, the "shipping point" applies. However, controlling inventory across a supply chain with different decoupling points for each entity is extremely challenging.

This is because, in the supply chain, downstream from the decoupling point (shipping) operates systematically based on orders, while upstream (procurement) relies on pre-planned strategies based on management decisions. Maintaining optimal inventory at the decoupling point requires the ability to avoid both excess inventory costs and opportunity losses from stockouts.

In Indonesia’s two- and four-wheeler industries, where just-in-time delivery (delivering the required quantity at the required time) is demanded by manufacturers, warehouse companies near manufacturers’ factories provide external warehousing services, including inventory management. Many parts manufacturers use these to reduce the risk of delivery delays due to severe traffic congestion.

Currently, Indonesia faces intense demand fluctuations due to rising and unstable international logistics costs, making optimal inventory maintenance even harder. However, similar to e-commerce and online marketplaces like Amazon, Alibaba, and Indonesia’s Tokopedia, Japanese general trading companies can devise logistics strategies to optimize the entire supply chain by overseeing and adjusting logistics. This contributes to consumer benefits through shorter order-to-delivery times and lower sales prices via economies of scale.