A production management system covers production activities from the receipt of materials into the material warehouse until they are processed in the manufacturing process, as well as sales activities from the product warehouse onward. The costs incurred as material costs and processing costs arise when materials are introduced into the manufacturing process, become manufacturing costs when turned into products, and become the cost of goods sold when shipped. Managing this series of cost flows is the role of a cost management system. Production Control System in Indonesia It’s not limited to Indonesia, but it’s often said that the ultimate goals of the manufacturing industry are twofold: "cost reduction through productivity improvement" and "delivering products on time without delays." From a management perspective, business plans are crafted to maximize growth based on market supply and demand adjustments. However, even if sales increase due to low pricing, it only reduces gross profit, leading to losses from selling and administrative expenses or non-operating costs. On the other hand, raising unit prices isn’t straightforward due to market price considerations. Therefore, process management based on production plans aimed at reducing costs through ... 続きを見る

Defining Requirements to Determine System Specifications

When introducing a production management system, there is a requirements definition phase to establish the operational flow of how the system will issue instructions and record performance based on on-site operational movements.

In the case of system implementation at a local Indonesian subsidiary, the requirements can be broadly divided into two approaches: a top-down pattern where all requirements are decided solely between the Japanese side, centered around the headquarters’ IT department, and the Japanese staff in Indonesia responsible for implementation (i.e., us), presenting the local Indonesian staff with, “Here’s a well-thought-out system designed by us Japanese, please use it”; or the traditional Indonesian musyawarah (consensus-building through discussion) approach, where Indonesian staff from each department engage in vigorous debates to seek a specification that represents the greatest common denominator.

- Top-Down Approach

Requirements definition is led by Japan to maintain standardized specifications across the group. - Musyawarah Approach

Since Indonesian staff will use the system, discussions are held locally until consensus is reached.

In the former case, strong leadership from the Japanese side and the expatriate Japanese at the local subsidiary can make it successful. However, if that’s not the case, or if staff dispatched by a partner due to the subsidiary’s capital structure hold sway, the implementation phase (translating the system post-requirements definition into operations) can face intense backlash.

Comments like, “We don’t do it this way in Indonesia,” or “The master data numbers are off, but that’s not our problem since the Japanese decided it,” are still relatively mild. Worse, a strange atmosphere might emerge with sentiments like, “They’re spending a fortune on this system, which is why our salaries aren’t going up,” and I’ve felt a subtle hostility while walking the site more than once or twice.

System Specifications Materializing On-Site

Everything is based on the requirements definition decided in these meeting room discussions. Gaps not covered by the system’s standard functions are addressed through add-on development. During operational briefings or training for the completed system, we listen to the raw feedback from on-site staff, making fine adjustments like specification changes or additional development. In operational rehearsals, where each departmental staff inputs data end-to-end from the start to finish of system operations, we confirm the inter-departmental coordination needed for actual operations.

In the implementation phase, where the system issues instructions (transfer, manufacturing, release, picking lists) aligned with the on-site movement of people and goods and records performance, there’s a sensation akin to a soul returning to its body after being detached—where the theoretical groundwork laid out so far takes physical form. If there’s any sense of fulfillment or joy in the job of implementing business systems, it’s precisely this moment.

However, during operations, unexpected issues not anticipated in the requirements definition, or issues with a far greater impact than expected, can create significant manual workloads for on-site staff, hindering the system’s operation just as it begins to run.

For example, if a label printer issuing product tags breaks down, instead of using dedicated label paper for a sticker system, we’d have to print labels on A4 paper from a regular multifunction printer and tape them to the products with Scotch tape to get by. Walking around a vast warehouse with Scotch tape and scissors to attach A4-sized labels to items is no small task (speaking from experience).

Implementation Tasks for Production Management Systems

Reflecting Inventory Based on Physical Counts and Moving Inventory to Designated Warehouse Locations

The first step in starting a production management system is reflecting inventory information in the system based on a physical inventory count. For manufacturers, only after confirming the quantity and location of material and resource inventory can the next schedule be set, such as, “From which date in which month will we start issuing manufacturing instructions via the system?”

There are two methods to attach product tags to all existing inventory in the warehouse:

- Conduct lot inspections for all lots entered during the inventory count and issue product tags.

- Backdate and input issued P/Os, then perform receiving inspections post-entry to issue product tags.

Materials or resources allocated by manufacturing instructions are linked as release instructions. When withdrawing them from the warehouse, scanning the barcode on the product tag records the release performance, so the barcode must at least include the item code and lot number.

To store items with product tags issued by the QC department after lot or receiving inspections in designated warehouse shelves, transfer instructions are issued. The shelf number is recorded in the transfer performance by scanning the barcode attached to the shelf during the item’s movement within the warehouse.

Generating Manufacturing Instructions by Creating an MPS from Order Data and Running MRP

Only after on-site inventory matches the system’s inventory can a Master Production Schedule (MPS) be created from order data and MRP run to generate manufacturing instructions aligned with the production batch size at the site. At this point, on-site staff typically raise two questions:

- Is the manufacturing start date shifted according to the current lead time?

- Does the manufacturing lot size match reality?

Once master data accuracy improves and system operations stabilize, tasks can be mechanically performed based on system-issued manufacturing instructions. However, immediately after implementation, ensuring the system issues manufacturing instructions aligned with on-site operations is critical to building trust in the system—i.e., making staff think, “This system seems usable.”

Issuing Release Instructions and Recording Release Performance

On-site, instructions might be issued by manufacturing staff but recorded by warehouse staff, and the timing of instructions and performance often differs. Thus, production management systems generally use a two-step process:

- Issue instructions and record performance (manufacturing, release, transfer)

- Create information and record performance (P/O, inspection)

As mentioned, release instructions are generated linked to manufacturing instructions, typically handled by manufacturing staff. Moving items from the warehouse to the manufacturing site is done by warehouse staff who can operate forklifts. Release instructions specify only the item code, lot number, and quantity. Which shelf the items are taken from is recorded in the transfer performance by warehouse staff scanning the barcode on the shelf during the task.

- Movement to warehouse: Specify From “item code + lot number” and To “warehouse” in instructions; record To “shelf number” in performance

- Movement from warehouse: Specify From “item code + lot number” and To “warehouse” in instructions; record From “shelf number” in performance

Recording Input Performance and Manufacturing Performance

With the backflush method, where the standard required quantity set in the BOM (Bill of Materials) is automatically input when recording production performance, all items in the factory can be identified by the production management system’s item codes. However, if there’s a timing gap between input and production performance recording, process inventory without item codes exists on-site:

- Work-in-progress with item codes

- In-process work-in-progress without item codes

Materials alone don’t become costs upon receipt, but once processing costs are added and they become work-in-progress, they are recorded as current-month expenses (costs) in accounting. If they remain as work-in-progress at month-end without becoming products, they are recorded as work-in-progress inventory (assets). When work-in-progress becomes products, it becomes the current-month manufacturing cost, and if unsold and lingering at month-end, it’s recorded as product inventory (assets).

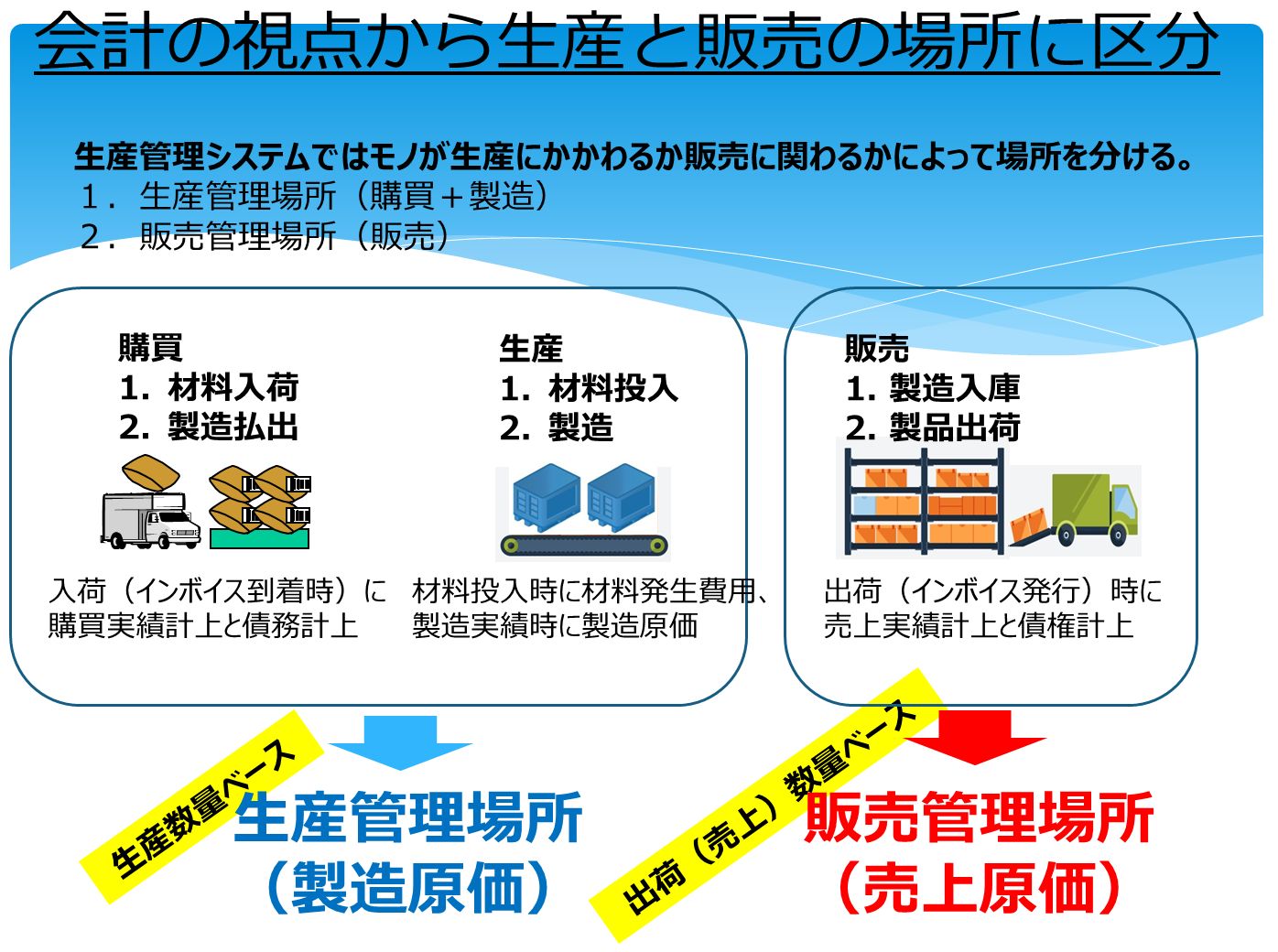

Production Management Up to Material Warehouse and Factory; Sales Management Beyond Product Warehouse

The functions of a production management system are broadly classified into three categories:

- Purchasing Management (Material Warehouse)

- Manufacturing Management (Factory)

- Sales Management (Product Warehouse)

Items stored by location are classified into two categories based on whether they relate to production or sales:

- Production Management (Material Warehouse and Factory)

- Sales Management

When manufacturing performance is recorded, items move from the production site to the sales site, entering the domain of sales management from that point onward.

Dividing into Production Management and Sales Management

Through production management’s receipt/payment performance, the manufacturing cost—how many products were made at what cost in the current month—can be calculated. Through sales management’s receipt/payment performance, the cost of goods sold—the cost of products actually sold and shipped from the beginning-of-month product inventory and current-month production output—can be determined.

- Total Average Product Unit Price = (Beginning-of-Month Product Inventory + Current-Month Manufacturing Cost) / (Beginning-of-Month Product Quantity + Current-Month Manufacturing Quantity)

- Cost of Goods Sold = Total Average Product Unit Price × Shipment Quantity

Sales management’s shipment performance is needed to calculate the cost of goods sold, and sales management’s sales performance is required to compute gross profit.

- Sales – Cost of Goods Sold = Gross Profit

Two Perspectives: Inventory Management and Cost Management

From the dual perspectives of inventory and cost, a factory is broadly divided into three locations, typically managed by different departments:

- Material Warehouse (RM Warehouse): Purchasing department manages receipt performance

- Manufacturing Process (Plant): Manufacturing department manages input and manufacturing performance

- Product Warehouse (Finished Goods Warehouse): Logistics department (sales department) manages shipment performance

To calculate manufacturing costs, the following information from the purchasing and manufacturing departments is required:

- Beginning-of-month inventory in the material warehouse

- Receipt performance in the material warehouse

- Beginning-of-month inventory in the manufacturing process

- Input performance in the manufacturing process

- Manufacturing performance in the manufacturing process

To calculate the cost of goods sold, the following information from the logistics (sales) department is needed:

- Beginning-of-month inventory in the product warehouse

- Entry performance in the product warehouse

- Shipment performance in the product warehouse

To calculate both manufacturing costs and the cost of goods sold, all information from the purchasing, manufacturing, and logistics (sales) departments is necessary.

All Receipt/Payment and Inventory Data Retain Department Information

All receipt/payment data in a business system retains the originating department, and inventory data resulting from receipt/payment and stored in the warehouse also retains the department information managing that location.

In a physical organization, Excel data from each department is emailed, compiled, and merged, requiring uniform target periods and formats across departments.

Similarly, performance data managed in a production management system is organized by department. To merge it and calculate gross profit, different department codes must be converted into a common department code.

Departments involved in receipt/payment in a production management system (purchasing, manufacturing, sales) correspond to the entities managing inventory locations on the organizational chart. However, in accounting or cost management systems, aggregation units like lines or product groups vary by purpose.

In the system, virtual overarching departments may be set up for report segmentation or permission separation, or fictitious shared departments may be created to record expenses that cannot be burdened on specific departments.

Instructions and Performance for Inventory Movement

At an Indonesian factory’s material warehouse, stacked materials are categorized by item, with handwritten stock cards tracking entry/exit history stored in binders. This handwritten history is recorded at the exact moment materials are released or received.

In other words, these stock cards are item-specific receipt/payment histories based on performance. However, before the warehouse staff physically handles and moves the materials, the manufacturing department staff must have requested, “Please release them,” prompted by a production management staff’s instruction to “Manufacture this.”

Obviously, to start production at the factory site, materials must be picked from the material warehouse, released, and moved to the site. These physical on-site movements correspond to the following in the production management system:

- Start production ⇒ Manufacturing instructions + Release instructions

- Pick materials at the material warehouse ⇒ Picking list

- Release and move to the site ⇒ Release performance

Omitting Release Input

With sufficient staffing, system operations could fully trace on-site movements. However, with rising labor costs in Indonesia in recent years, reducing indirect department labor costs has become a key issue. Excess personnel are rare, and inputting data so meticulously is pointless if it’s not utilized.

Thus, instead of allocating releases during manufacturing instructions, standard input quantities matching output are calculated from the BOM and automatically deducted when recording manufacturing performance (backflush). Alternatively, defining the material warehouse as a process warehouse to maintain continuity with the manufacturing site eliminates releases altogether, reducing the system’s operational burden.

However, standard quantities are theoretical, and maintaining inventory accuracy requires periodic adjustments for differences with physical inventory.

The Purpose of Issuing Instructions and Recording Performance

The purpose of “issuing instructions and recording performance” is to separate the management (e.g., responsible staff or timing) of instruction input and performance input for some reason. Inventory movements that seem to warrant such management might include the following four:

- Releasing materials allocated by manufacturing instructions from the material warehouse to the manufacturing site ⇒ Release instruction

- Releasing materials or work-in-progress allocated by a PO to an subcontractor from the warehouse to the subcontractor ⇒ Subcontractor release instruction

- Inventory movement between warehouses ⇒ Transfer instruction

- Disposal ⇒ Disposal instruction

The Role of Inventory Management

The importance of inventory management in business operations goes without saying, and inventory management systems are introduced to streamline these tasks and effectively utilize inventory data.

Systemizing the receipt of goods or materials that will become inventory, daily production line performance collection, and shipping to customers forms an integrated business system (ERP) centered on inventory management. IT devices like barcode readers, handheld terminals, POP terminals, and iPads are used to simplify data entry.

Inventory management is at the core of business workflows, closely tied to all sales, purchasing, and production tasks. Successful systemization significantly enhances the accuracy of internal business data and operational efficiency.

In manufacturing inventory management, when receipt/payment for the three item types—materials, work-in-progress, and products—is handled via the inventory management system’s performance input function, questions arise: Are entry (input performance) and release (production performance) manually entered? Does recording production performance automatically record input performance? This requires a Bill of Materials (BOM), but to what level should the BOM be set? Thorough requirements definition is essential for implementing an inventory management system in manufacturing.

For first-time implementation of an inventory management system in manufacturing, starting with receipt/payment input for materials and products only, reflecting work-in-progress from month-end inventory counts, and gradually expanding to manage in-process inventory reduces the on-site burden.

Cost Management in Inventory Management Systems

Business workflows involve two streams—quantity and amount. Inventory management systems manage the quantity stream, with the following three main functions:

- Current inventory list

- Receipt/payment history management (stock card)

- Receipt/payment performance input

For non-manufacturing sales businesses managing purchased goods’ entry/exit and costs (unit prices) in real-time, the choice is between calculating with the moving average method in real-time or managing by lot with the FIFO method using purchase costs.

When cost management intersects with inventory management, the purchase cost of goods isn’t just the purchase price—incidental costs like shipping or customs clearance fees (purchase overheads) must be considered. If the amounts are small, they might be treated as SG&A expenses, but for imports with high incidental cost ratios, the challenge is how to allocate these to items within the inventory management system.

In sales businesses, goods are purchased, a margin is added, and they’re sold. In manufacturing, materials are purchased, input into the manufacturing process, become work-in-progress, then products. While material costs can be managed similarly, managing the costs of work-in-progress and products in the manufacturing process is less straightforward.

Even if material unit prices are calculated in real-time with the moving average, labor and overhead costs are finalized at month-end. Reflecting these in unit prices in real-time during the month requires standard costs, with adjustments at month-end to allocate differences between actual and standard costs to the cost of goods sold and ending inventory.

In actual cost accounting, material, labor, and overhead costs are all calculated in batch at month-end. Material costs are computed as “monthly total average unit price × actual input quantity,” while labor and overhead costs are apportioned based on labor hours from the ledger (G/L) balances of relevant accounts aggregated in the accounting system.

Two-Directional Business Flows Arising from Purchasing

Inventory valuation methods mainly include Monthly Average and Moving Average. To update the latest average unit price in real-time with the moving average method and determine sales prices with a margin, entries must be input in date order, posing a constraint.

The invoice arrival date from the supplier is the posting date for accounts payable (A/P). However, accounting staff want to track transactions that will soon become A/P during the period between receipt and invoice arrival. To manage this, an A/P Accrued (unrealized liability) account is used to accumulate costs at receipt, then reclassified to A/P upon invoice arrival.

Inventory Management Flow

- Increases inventory quantity of goods

- Updates unit price of goods (in the case of moving average)

Accounting Flow

Journal entry at receipt:

- (Dr) Purchase 10,000 (Cr) A/P Accrued 10,000

- (Purchase) (A/P Accrued)

Journal entry at invoice arrival:

- (Dr) A/P Accrued 10,000 (Cr) Accounts Payable 10,000

- (A/P Accrued) (A/P)

Handling Indirect Costs

If the unit price of purchased items consists solely of the purchase amount on the purchase order (P/O), there’s no issue. However, typically, CIF (Cost, Insurance, and Freight) costs arise, such as shipping, customs duties (Bea Masuk) in the Import Declaration (Pemberitahuan Impor Barang = PIB), PPh21, or clearance permits (Surat Persetujuan Pengeluaran Barang = SPPB).

There are two main methods to handle these purchase overheads:

Recording as Expenses at Occurrence (Small Amounts)

- (Dr) Purchase Overheads 400 (Cr) Customs Agent Payable 400

- (Expense) (A/P Accrued)

Recording as Cost of Goods Sold at Sale (Large Amounts)

- (Dr) Purchase 7,000 (Cr) Forwarder Payable 7,000

- (Purchasing) (A/P Accrued)

Recording in the purchase account means including the forwarder’s invoice amount in the total cost of inventory assets in the month-end closing entry. Thus, there’s no need for detailed processing like allocating indirect costs to individual items in the accounting entry at the transaction point—nor is there a need to separate accounting entries by item.

Implementing Item Allocation of Indirect Costs in the System

While there’s no need to allocate indirect costs to items in accounting entries at the transaction point, determining an appropriate sales price at a given moment may require:

- Updating the moving average unit price by reflecting CIF costs each time.

- Automatically calculating item unit prices reflecting CIF costs in the inventory management system for ending inventory valuation.

For these reasons, if indirect costs need to be allocated to item unit prices per transaction in the inventory management system, deciding which screen to input them from becomes a challenge.

The issue here is that indirect cost amounts aren’t necessarily known at the time of ordering (P/O issuance) or receipt. For instance, if a forwarder’s invoice arrives two weeks after shipment, inputting indirect costs in the purchasing system at the time of ordering or receipt isn’t feasible.

Adding a Field (Separate Tab) for Purchase Overheads on the Receipt Screen

The downside is that input becomes locked once the receipt entry is posted to the ledger. In such cases, posting can be pending, or adjustments made post-posting. This method is commonly used in commercial ERP packages.

Linking with P/O Number, Receipt Number, or Invoice Number via Direct Invoice Function

The Direct Invoice function allows posting A/P without issuing a P/O or processing receipt. Linking it to a key identifying the item enables allocation of indirect costs to items.

Processing as Purchase of Services (Non-Inventory Items = Uncounted Items) via Purchasing Module

This involves processing receipt after P/O issuance or using the Purchase Direct function without a P/O to link with the item’s P/O. In this case, costs manageable in the inventory management system are limited to purchased goods.

Factors Causing Document Linkage Breaks

Returning to the system workflow for domestic transactions, if all documents (slips) correspond one-to-one, the flow becomes efficient as follows:

- Order registration assigns an order number.

- Selecting the order number during purchase order registration retrieves order information.

- Selecting the purchase order number during receipt registration retrieves purchase order information.

- Selecting the receipt number during shipment registration retrieves receipt information.

- Selecting the shipment number during invoicing retrieves shipment information.

- Selecting the invoice number during payment registration retrieves invoice information.

If a system registers sales during order or shipment management, invoice registration in accounting is skipped, and A/R arises at the sales registration point.

Typically, orders and purchase orders aren’t linked, but in non-manufacturing businesses (e.g., trading companies), transactions often involve purchase orders based on orders. Direct shipment from the manufacturer results in dropshipping, skipping receipt and shipment.

When developing a production management system, the following processes should be carefully managed to avoid breaking document linkages in the workflow:

- Purchase Order

- Speculative ordering before receiving an order

- Allocating inventory without ordering

- Consolidating multiple orders into one purchase order - Receipt

- Shipment

- Partial delivery

- Order cancellation

- Returns

- Consolidating multiple orders (purchase orders) into one shipment (receipt)

- Sample shipment (receipt) from inventory before an order - Invoice (A/R)

- Consolidating multiple shipments into one invoice (monthly summary)