While the recognition of production schedulers in Indonesia is still low, they address core production management tasks—such as daily load calculations for sub-resources like molds and personnel, and creating production schedules for main resources like machines with those as constraints—that even expensive ERP packages cannot handle. Production Scheduler in Indonesia In Indonesia's Japanese manufacturing industry, the adoption of production management systems has been increasing. However, when it comes to one of the key challenges in production management—creating feasible production plans that take machine and equipment loads into account—manual work using Excel remains the standard practice. As a result, the demand for production schedulers is expected to grow in the future. 続きを見る

Pre-Sales of Production Schedulers in Indonesia

I work in technical sales for Asprova, a production scheduler application for manufacturing, in Indonesia. Due to its low recognition here, it’s hard for prospects to envision its cost-effectiveness. While I wouldn’t say they start with outright rejection, presentations and demos usually begin from a negative baseline.

Hearing this daily can make sales pitches feel defensive.

However, production schedulers can do two things that costly production management packages cannot:

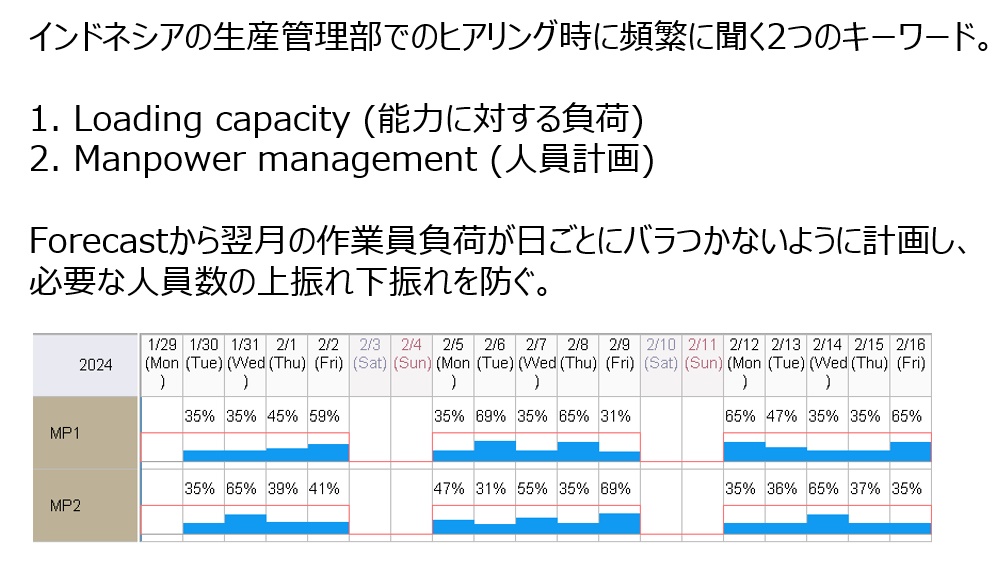

- Calculate loads for production resources—personnel, machines, molds, trollies, etc.—from monthly to daily levels based on forecasts.

- Create daily production schedules based on confirmed orders, factoring in the constraints from point 1.

In truth, these two functions are the core of manufacturing production management. One could argue, “It’s incredibly well-regarded because it does this at a fraction of the cost of production management packages—don’t you know that?” or “It’s such a cost-effective choice; it’s rare not to go with it” (though I’d phrase it more politely in practice).

That said, I believe the success of production management package implementation hinges on master data and inventory accuracy. Without reliable data, implementing a production scheduler is challenging—this is a key premise.

That said, I believe the success of production management package implementation hinges on master data and inventory accuracy. Without reliable data, implementing a production scheduler is challenging—this is a key premise.

In China, there’s a saying, “Beat the chicken to scold the dog”—poor chicken—but with production schedulers, I adopt a slightly passive-aggressive sales approach, or rather, a pull strategy.

The Significance of Japanese Engineers (SEs) in Indonesia

When selling systems to Indonesian factories, it’s common for a Japanese decision-maker and an Indonesian staff member to attend from the client side. I explain in Indonesian to the local staff, interspersing Japanese at key points to appeal to the Japanese decision-maker. Anticipating typical questions from Indonesian staff and weaving them into the demo is crucial, so I can pull out a “Yes, here it is” demonstration from my pocket when asked.

This raises the question: Is there a need for Japanese SEs in Indonesia? First, Japanese salespeople are essential. Selling to Japanese firms means pitching to Japanese decision-makers, which only a Japanese person can effectively do—unless it’s a rare global company where English is the lingua franca and nationality or native language doesn’t matter. In Indonesia’s Japanese expatriate community, I believe a highly communicative Japanese salesperson is indispensable.

But what about SEs? Frankly, Indonesia has tons of highly skilled locals. It’s easier to find an Indonesian SE more capable than a Japanese one than to find an exceptional Japanese SE here. Thus, Japanese SEs in Indonesia inevitably need sales skills.

If it’s just technical expertise, Indonesians are better and cheaper. My view: Japanese SEs aren’t necessary here.

For orders, a Japanese salesperson conducts marketing, then brings an Indonesian technician to demo for promising prospects, earning sufficient trust. While sales needs some technical knowledge, spending years studying tech is less efficient than focusing on list marketing or golf networking to win deals.

Given this, the significance of a Japanese SE in Indonesia might be providing clients with, “There’s a Japanese tech expert, so I can ask questions in Japanese if needed”—a sense of reassurance. Performing demos as a Japanese might reinforce this.

I demo in Indonesian for local staff, but even after a self-satisfying demo, I’m always asked, “No Indonesian technicians?” Indonesians want to ask in Indonesian, Japanese in Japanese.

Even in Indonesia, where English is widely used and globalization outpaces Japan, it’s still “mother tongue, no matter what.”

Challenges in Explaining a Lesser-Known Production Scheduler in Indonesia

With production management systems, processing flows are somewhat predictable. Clients often know more than sellers about what they are, can do, and cannot do. Post-implementation pitches focus on, “Your daily workflow will look like this, you’ll get this info, you’ll enable this analysis.”

For unexpected questions like “Can it do this?”—unless it’s extremely complex—I can say, “Not with the standard package, but customization or add-on subsystems can make it possible.” Clients can’t demand more on the spot, avoiding negative “No” answers and keeping demos smooth.

But with a production scheduler, less known in Indonesia, it’s different. It starts with “What’s a production scheduler?”—requiring explanations of capabilities and limits. Questions like “How’s it different from a production management system?” “It manages inventory too, right?” “It comes with lots of standard reports, doesn’t it?” assume “It’s probably like a production management system.”

When asked, “It manages inventory, right?” or “Show me standard P/O and invoice formats,” I can only say, “No, it doesn’t” or “That’s not its purpose”—it’s not built for that. Unlike production management systems, I must clearly state, “What it can’t do, it can’t do.”

This makes demos prone to derailment. Clearing the first hurdle—convincing clients “A production scheduler lacks inventory management or invoice issuance like a production management system”—finally allows demos and evaluations of its true functions.

Production management systems analyze current conditions with past data, while production schedulers use parameter settings for repeated rescheduling to achieve desired outcomes. When clients ask, “Can it do this?” even if possible, failing to demo it on the spot is as good as “No.”

Clients demand demos for real shop-floor scenarios—“Finish parts for ASSY a day earlier,” “Assign to a sub-molding machine if the main one’s full,” “Show handling a broken press,” “Batch same items to reduce setups,” “How do you handle NG items in performance data?”—saying, “Show it now with that scheduler you’re pitching.” This is the second hurdle.

Production scheduler demos typically face these two barriers, making them challenging.

The Biggest Reason Production Scheduler Demos Are Difficult

The above hurdles involve interpersonal dynamics, but the biggest reason production scheduler demos are tough lies in the system’s inherent nature.

Production management systems, as “current analysis systems based on performance data,” must produce logical, trustworthy results. Production schedulers, however, “repeatedly reschedule using parameter settings to approach desired results,” with numerous properties in planning parameters, masters, and orders—making influencing factors highly complex.

The evaluation process for assigning resources involves many elements, so even “correctly” weighting properties doesn’t guarantee an optimal schedule—it merely trends results in a direction.

Getting the desired schedule often requires trial and error, like taming a wild horse.

A common demo misconception is, “Your system automatically creates the optimal schedule for our factory, right?”—expecting an AI engine to judge optimality from preset resource parameters and orders, delivering the planner’s ideal result. That’s impossible.

Optimizing production plans might broadly mean “a leveled plan without capacity overload or delivery delays,” but in Indonesia—prone to demand swings, currency fluctuations, and logistics chaos—the biggest issue is equipment line stoppages from raw material shortages. Issuing production instructions to avoid stoppages, considering raw material inventory (absolute quantity) and open purchase orders (increase/decrease), is key.

“What’s optimization?” is like “What’s the world’s best food?”—answers vary by person, time, and place. Rarely can one envision the optimal schedule during rescheduling, so a production scheduler’s role may be to assist in finding “what’s optimal” for the current shop floor.

Scheduling Directions in Boom and Bust Times

Production management systems typically divide management by process (location), matching shop-floor or building separations. Physical distances or walls between processes hinder material and information flows, limiting lead time and work-in-progress reductions.

Conversely, production schedulers visualize end-to-end process flows, fostering production flow and overall optimization awareness. Clarifying material requirements and process input timing reduces inter-process inventory.

In booming Indonesia, throughput maximization trumps inventory or lead time reduction. While human instinct might cram short orders into idle equipment, production schedulers simulate capacity maximization with existing resources.

During busts—like post-Lehman or China’s demand slowdown—when domestic manufacturing demand drops, operators may feign busyness, creating waste. Production schedulers logically reveal true busyness, enabling decisions like “If idle, don’t produce excess—do other tasks.”

In Indonesia, labor disputes halting production can delay deliveries and harm clients. Preparing a BCP (Business Continuity Plan) for contingencies, while reflecting incidents in the scheduler for rescheduling, helps devise specific countermeasures.