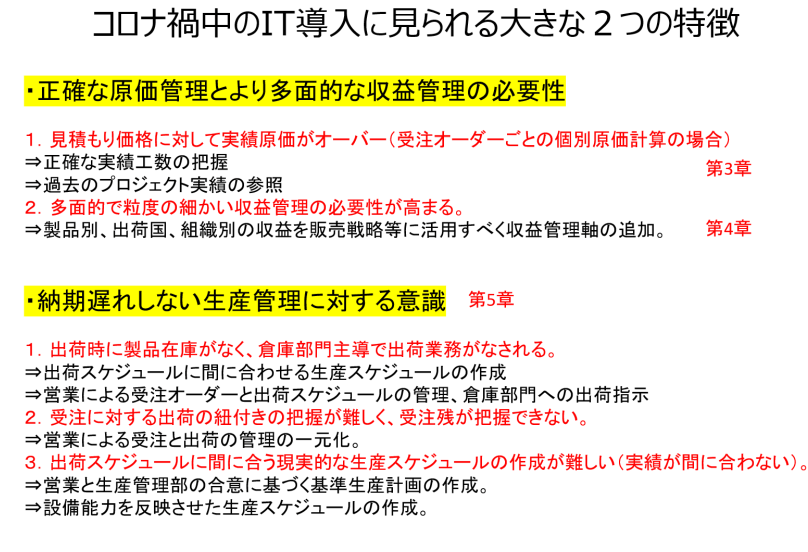

Amid Indonesia’s COVID-19 pandemic, trends in systemization (DX) consultations from Japanese manufacturing companies highlight two key points: the need for accurate cost management and more multifaceted profit management, and an awareness of production management that prevents delivery delays. Production Scheduler in Indonesia In Indonesia's Japanese manufacturing industry, the adoption of production management systems has been increasing. However, when it comes to one of the key challenges in production management—creating feasible production plans that take machine and equipment loads into account—manual work using Excel remains the standard practice. As a result, the demand for production schedulers is expected to grow in the future. 続きを見る

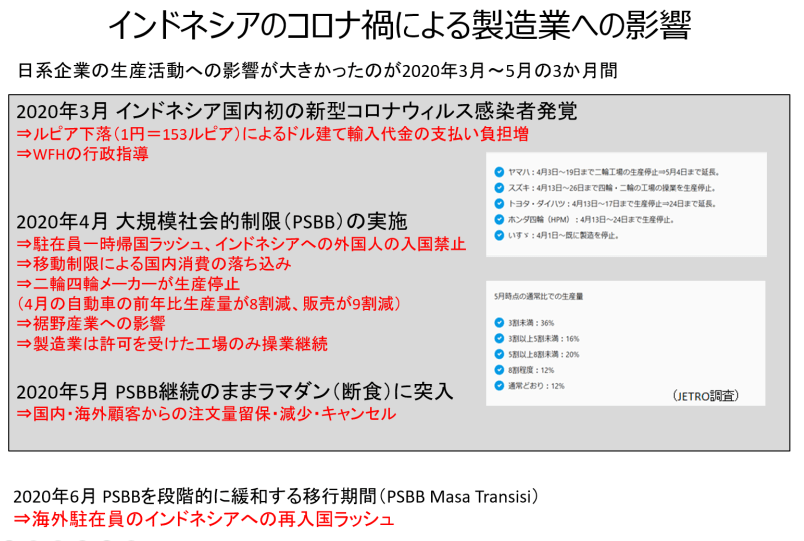

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Manufacturing in Indonesia

In March 2020, Indonesia confirmed its first COVID-19 case. By April, large-scale social restrictions (PSBB) limited human movement, reducing consumption. May saw PSBB continue into Ramadan, with 32% of Japanese manufacturers facing over 50% production cuts due to order holds, reductions, or cancellations from domestic and international markets. The impact on production activities from March to May was truly significant.

In March 2020, Indonesia confirmed its first COVID-19 case. By April, large-scale social restrictions (PSBB) limited human movement, reducing consumption. May saw PSBB continue into Ramadan, with 32% of Japanese manufacturers facing over 50% production cuts due to order holds, reductions, or cancellations from domestic and international markets. The impact on production activities from March to May was truly significant.

Indonesia has faced economic downturns before—1998’s currency crisis, social unrest from frequent bombings since 2002, and the 2008 Lehman Shock—each time damaging the real economy of production, distribution, and consumption. My experience suggests private-sector IT investment lags real economic recovery by six months.

In June, Indonesia entered a transitional PSBB phase (PSBB Masa Transisi), easing restrictions gradually and marking a shift to a “New Normal.” By late June to July, with expatriates rushing back to Indonesia, I braced myself for manufacturing IT investment to pick up no earlier than December.

From late October, inquiries and leads slowly returned, but turning them into projects with down payment (DP) invoices took 1-2 months, and payment another month. The struggles of service businesses targeting local companies are beyond imagination.

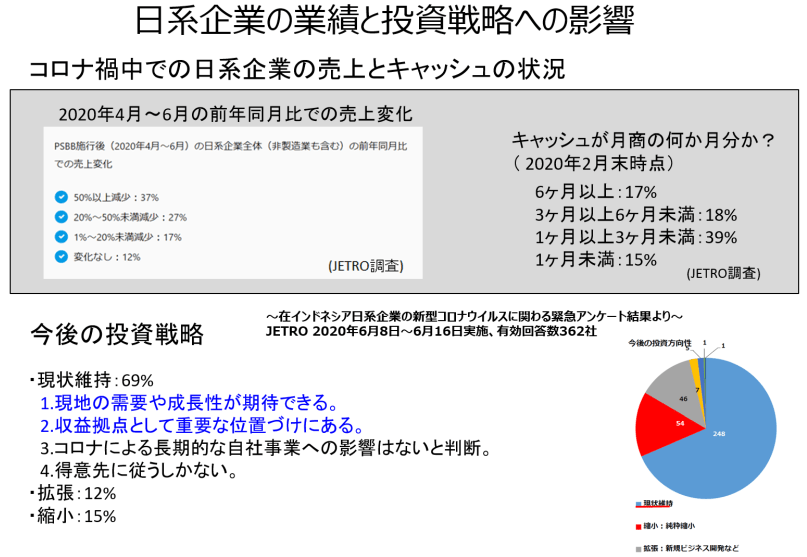

Impact on Japanese Companies’ Performance and Investment Strategies

According to JETRO’s survey, 37% of Japanese companies in Indonesia saw sales drop over 50% year-on-year in Q2 2020, while 27% experienced a 20%-50% decline. Meanwhile, 55% had cash reserves below three months of sales as of late February 2020. Naturally, this heavily impacts IT investment strategies that don’t generate immediate cash.

According to JETRO’s survey, 37% of Japanese companies in Indonesia saw sales drop over 50% year-on-year in Q2 2020, while 27% experienced a 20%-50% decline. Meanwhile, 55% had cash reserves below three months of sales as of late February 2020. Naturally, this heavily impacts IT investment strategies that don’t generate immediate cash.

Surprisingly, future investment strategies showed little negative impact. With expectations of local demand and growth potential, and Indonesia’s importance as a profit base, 69% of companies planned to maintain operations, 12% considered expansion, and only 15% contemplated downsizing.

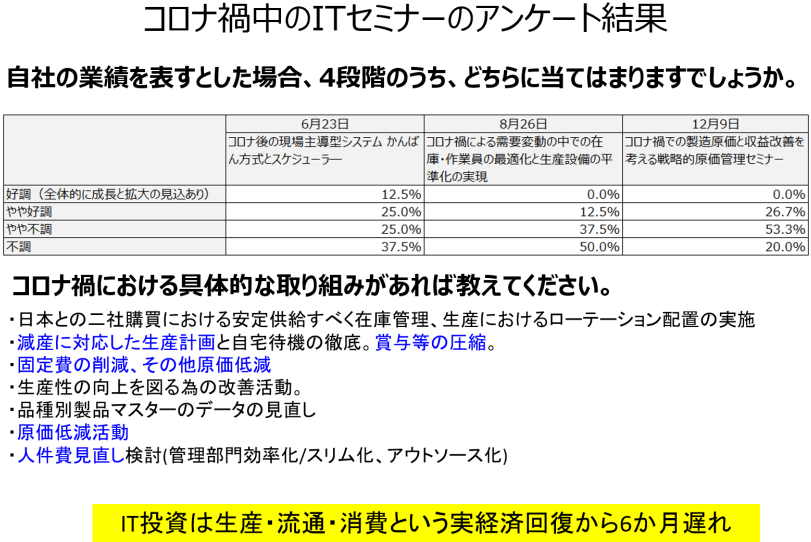

From questionnaires at three seminars held during the pandemic, business improvement initiatives included:

From questionnaires at three seminars held during the pandemic, business improvement initiatives included:

- Production rotation scheduling

- Production plans adjusted for reduced output and strict stay-at-home policies, bonus compression

- Management department efficiency/slimming, outsourcing

- Productivity improvement activities

- Review of product master data by category

This reflects a heightened awareness of cost management and production planning, evident in inquiries to our company:

- Actual costs exceeding quoted prices

- Need for multifaceted, granular profit management

- Product inventory shortages at shipment

- Tracking linkage between orders and shipments

- Realistic plans ensuring on-time shipment

Cost Aggregation in Make-to-Order Factories

Of 1,489 Japanese companies in Indonesia, 871 are manufacturers (November 2019), with 25% in the two- and four-wheeler sectors.

Of 1,489 Japanese companies in Indonesia, 871 are manufacturers (November 2019), with 25% in the two- and four-wheeler sectors.

During the pandemic, customer awareness in inquiries focused on:

- Need for accurate cost management and more multifaceted profit management

- Need for production management preventing delivery delays

These two points stood out.

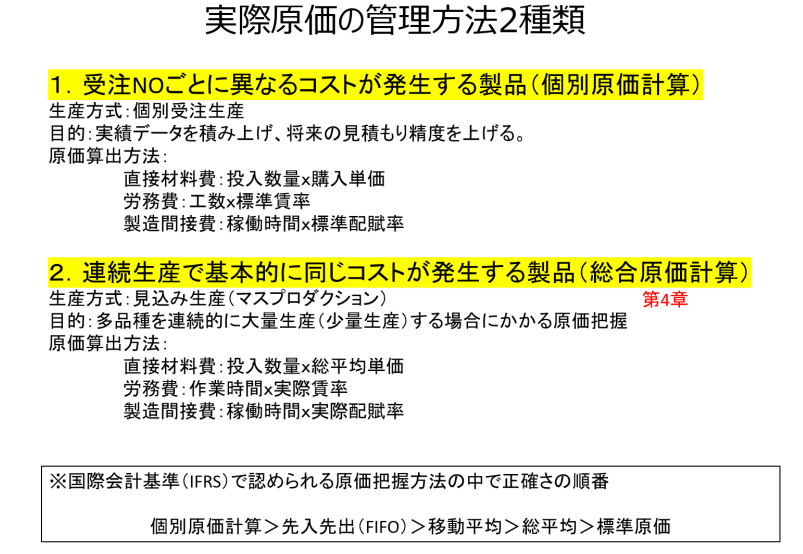

Factory production methods split into make-to-order (MTO), where costs vary per order number, and mass production, where costs are generally uniform.

Make-to-order is common in SMEs, aiming to improve future quote accuracy by accumulating performance data.

Make-to-order is common in SMEs, aiming to improve future quote accuracy by accumulating performance data.

In one-off MTO factories, detailed blueprints often aren’t available at quoting, and accurate material costs are calculated post-order based on detailed designs from the client. Thus, the volume and systematic accumulation of useful past performance data for budgeting at the quoting stage are critical.

Japanese SMEs in Indonesia doing MTO could once dominate markets with unique, high-skill “town factory techniques,” allowing rough cost estimates with hefty margins to secure orders.

Now, it’s an era of fierce competition with local firms and companies from China, Taiwan, Singapore, and Korea.

With all due respect, my candid impression is that despite their technical prowess, companies still clinging to the cost mindset of a few years ago—when merely setting up a factory in Indonesia brought inquiries—are struggling in today’s price-competitive landscape.

I don’t believe DX is always the solution. However, as symbolized by the “FAX issue,” the pandemic exposed Japan’s DX lag, with vested interests and past ties hindering progress—a sentiment strongly felt at the operational level, underpinned by differences in decision-making speed.

Indonesia, free from legacy system constraints or vested interests, saw rapid EC and mobile system adoption. In Japan, generational shifts from Baby Boomers to their successors will surely accelerate reform decisions. We must face harsh realities and move forward.

Cost Aggregation in Continuous Mass Production

During the pandemic, many Japanese manufacturers sought system導入検討 for cost management reviews. Compared to a decade ago, Indonesia’s prominence as a manufacturing and sales hub has grown, and with rising labor costs, IT budgets for local subsidiaries seem more readily approved.

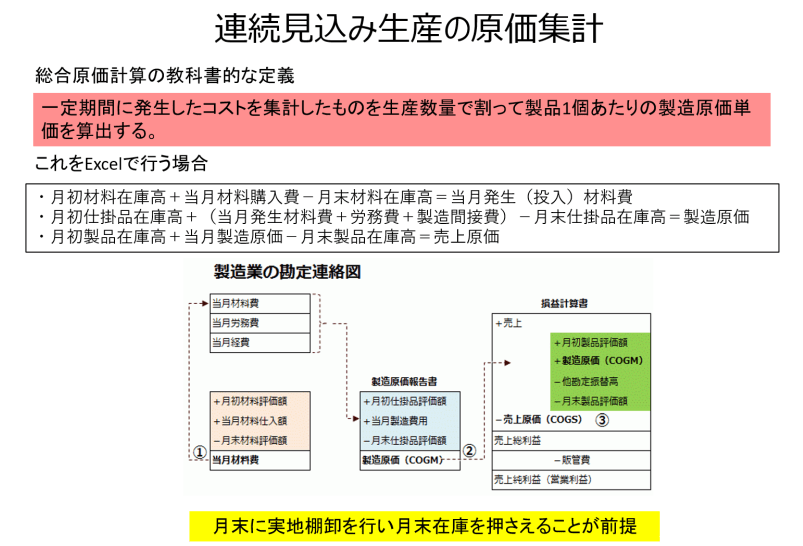

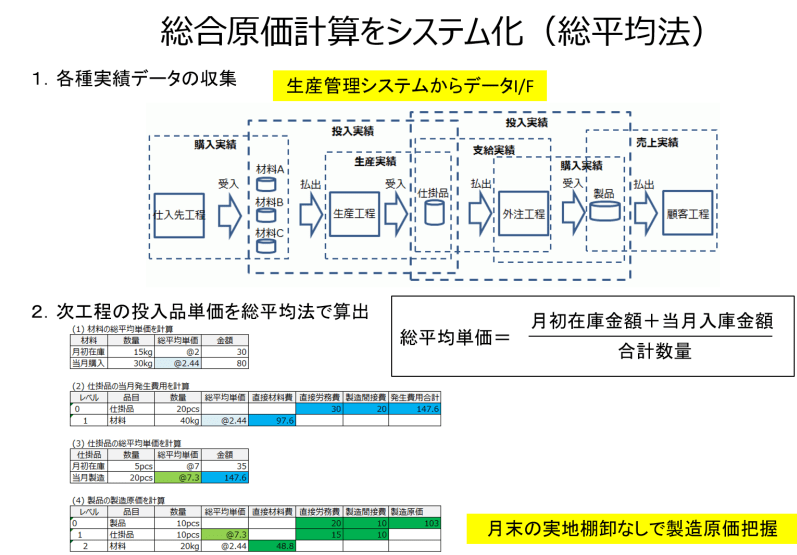

In recent years, core operations of Japanese firms in Indonesia have gradually systemized. Currently, one area least impacted by the DX wave is cost management, especially mass-production process costing. This is because adopting IFRS-approved methods like total average or moving average requires accurate production performance data.

In recent years, core operations of Japanese firms in Indonesia have gradually systemized. Currently, one area least impacted by the DX wave is cost management, especially mass-production process costing. This is because adopting IFRS-approved methods like total average or moving average requires accurate production performance data.

Process costing details can’t be summed up briefly, but the pandemic raised more fundamental questions: “Why grasp costs accurately?” and “What do you want to do with it?” Beyond lofty goals like social responsibility, a company’s purpose is profit pursuit—a condition for survival.

Process costing details can’t be summed up briefly, but the pandemic raised more fundamental questions: “Why grasp costs accurately?” and “What do you want to do with it?” Beyond lofty goals like social responsibility, a company’s purpose is profit pursuit—a condition for survival.

Profit ensures survival—securing cash and deposits. Starting with 100 juta in capital and 25 juta monthly fixed costs, without sales within four months (even in cash transactions), it’s game over. Hence, layoffs (PHK) and salary cuts (Potong Gaji) to avoid cash shortages.

Merely grasping costs accurately doesn’t increase profit by a single rupiah. What matters is how much profit those costs generate. On-balance-sheet, it’s ROI (return on investment), necessitating a shift from cost-center to profit-center thinking.

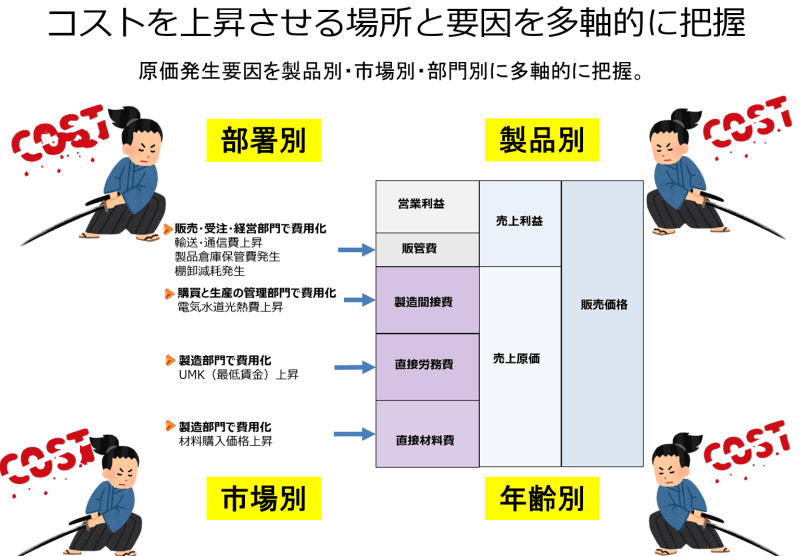

This mindset shift means calculating gross profit from manufacturing costs on the P/L, subtracting SG&A for operating profit, and judging cost validity vertically on the P/L—a managerial accounting approach. Furthermore, pandemic-era profit improvement demands multi-axis analysis expanding the P/L’s horizontal scope.

This mindset shift means calculating gross profit from manufacturing costs on the P/L, subtracting SG&A for operating profit, and judging cost validity vertically on the P/L—a managerial accounting approach. Furthermore, pandemic-era profit improvement demands multi-axis analysis expanding the P/L’s horizontal scope.

Production Management Preventing Delivery Delays

During the pandemic, Japanese manufacturers cited two key improvement challenges: “accurate, multifaceted cost management” and “the need for production management preventing delivery delays.” In manufacturing, production management covers raw material procurement to product completion, while sales management handles order receipt to shipment.

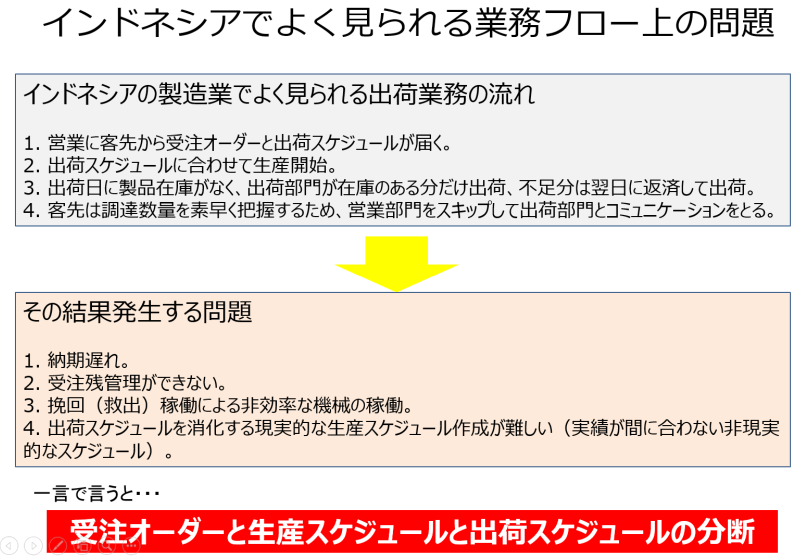

A common operational pattern in Indonesian manufacturing:

- Sales receives customer orders and shipment schedules.

- Production starts per the shipment schedule.

- On shipment day, insufficient product inventory forces the shipping department to ship what’s available, covering shortages the next day.

- Customers communicate directly with the shipping department.

This narrows sales’ scope to order management. Ideally, sales should collaborate with production management to create the Master Production Schedule (based on product completion dates), issue shipping instructions, and manage order fulfillment and backlogs.

Sales should lead invoice issuance to customers, passing sales slips to accounting for revenue and receivable postings. However, inability to manage order backlogs delays this, waiting for shipping’s completion and updates. The root issue is insufficient product inventory at shipment and failure to produce on schedule.

Sales should lead invoice issuance to customers, passing sales slips to accounting for revenue and receivable postings. However, inability to manage order backlogs delays this, waiting for shipping’s completion and updates. The root issue is insufficient product inventory at shipment and failure to produce on schedule.

Since products aren’t always ready at shipment, many factories shift customer contact from sales to shipping staff, disconnecting order, shipment, and production (and procurement) schedules. This causes delivery delays, reducing productivity through recovery production.

What DX Means During the Pandemic

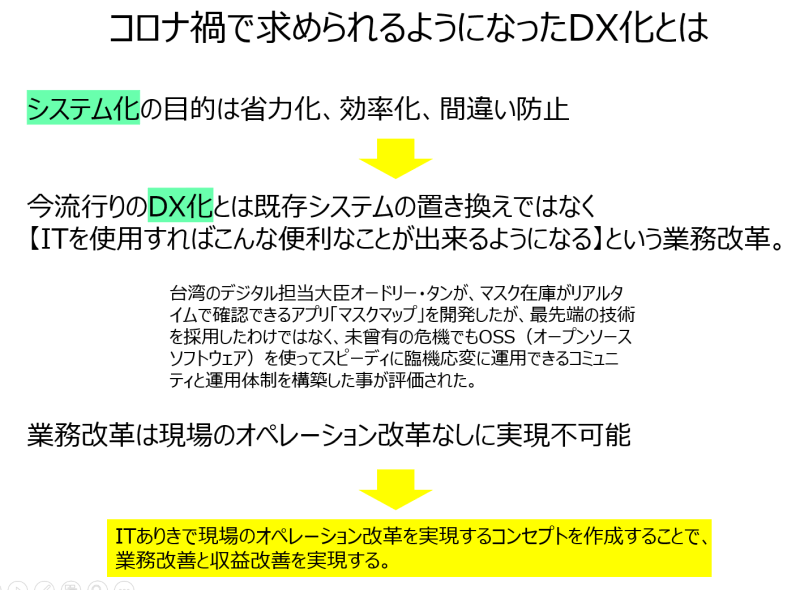

If systemization aims for labor savings, efficiency, and error prevention, today’s trending DX isn’t just replacing old systems but a business reform enabling [“With IT, we can do these convenient things”].

If systemization aims for labor savings, efficiency, and error prevention, today’s trending DX isn’t just replacing old systems but a business reform enabling [“With IT, we can do these convenient things”].

Taiwan’s Digital Minister Audrey Tang developed the “Mask Map” app for real-time mask inventory checks, curbing shortages, hoarding, and reselling. Rather than cutting-edge tech, this leveraged OSS (open-source software) for swift, flexible government response, earning praise for building an adaptive community and operational framework.

Business reform requires operational reform at the ground level. Creating a concept for operational reform via IT to achieve business and profit improvements is, I believe, the profound significance of DX.