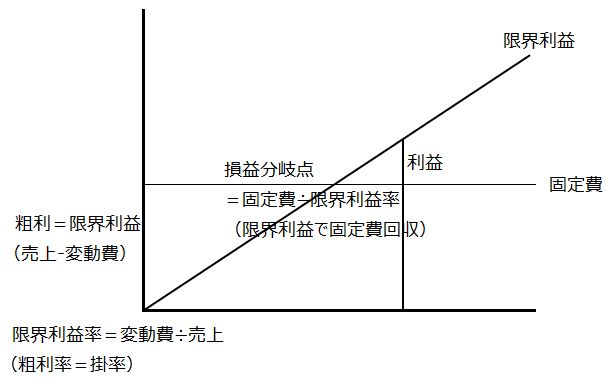

Costs can be divided into variable costs and fixed costs. The break-even point sales, which recover fixed costs, are determined by the marginal profit rate—the ratio of the purchase price (variable cost) to sales. In other words, direct costing calculates how many clothes need to be sold to achieve the break-even point sales, considering only variable costs as the original cost. Cost Management in Indonesia Mass production factories, such as two- and four-wheeler parts manufacturers common in Indonesia, have multiple manufacturing processes. In such cases, processing costs are calculated for each process, and the method of aggregating these costs into the product is called process costing. In this approach, labor costs and manufacturing overheads are recorded at the end of the month by the accounting department, transferred to inventory assets, and then allocated accordingly. On the other hand, in factories producing custom-made items under individual order production, job order costing is used, where costs are aggregated by order number or project number. In this case, ... 続きを見る

The Break-Even Point: No Profit, No Loss

Up until eight years ago, I ran boutiques in Ramayana Mall in Denpasar, Bali, and on Danau Tamblingan Street in Sanur. My strategy back then was a "time machine business," taking advantage of the fact that "Jakarta trends arrive in Bali three months late."

Every month, I’d buy the latest trendy imported Chinese clothing models from a wholesale store in Mangga Dua, Jakarta, ship them to Bali via DAKOTA cargo on the spot, and have them on display in the store within a week. Women’s clothing, especially trendy items for ABG (Anak Baru Gede, or teenagers), is like perishables—freshness is everything.

In simple terms, the break-even point is how many items (or how much money) I needed to sell to cover rent and labor costs, reaching a state of "no profit, no loss."

- Sales − Variable Costs = Fixed Costs

- Marginal Profit = Fixed Costs

My wife handled purchasing and sales, I managed transportation and accounting, and the store operated on two shifts with five SPGs (Sales Promotion Girls). Each SPG’s salary was 800,000 rupiah per person. Looking back, it feels pretty exploitative.

As the accountant, my first thought was:

- Use OMSET (sales revenue) to cover tenant rent of 7 juta and labor costs of 4 juta

In reality, the tenant rent was prepaid for a year, so we wouldn’t run out of cash by the end of the month, but I calculated it monthly as a fixed cost at month-end. Since we easily surpassed 11 juta in monthly sales, this was a breeze to clear.

The next thing to consider was:

- Use OMSET − MODAL (the purchase cost within the cost of sales), i.e., Profit, to recover tenant rent of 7 juta and labor costs of 4 juta

This is where things started to get a bit tough.

Since MODAL is "MODAL relative to OMSET," it becomes:

- MODAL = Beginning-of-month inventory + Monthly purchases − End-of-month inventory

This is exactly the variable cost (equivalent to direct material costs in manufacturing).

Clothes were generally sold at about 60% markup, so the profit margin was 0.4. Therefore, ideally:

- 11 juta ÷ 0.4 = 27 juta

You’d need to hit around 27 juta in sales to reach the break-even point—"no profit, no loss." This 0.4 profit margin relative to the purchase price is called the marginal profit rate.

Well, that’s an impossible game, so we settled at around 22 juta in OMSET and felt somewhat relieved.

Running a store lazily in warm Bali, you tend to forget the initial investment (the first year’s tenant rent) and focus on clearing month-end payments with a bit of profit left over. But as the tenant rent renewal for the next year approached, reality sank in, and panic started to set in.

Sales Enough to Recover Fixed Costs

The break-even point concept is about "the number of clothes or sales amount needed to recover monthly tenant rent and labor costs." Essentially, it’s about "at least generating enough sales to avoid a loss." For a small retailer like us, it makes sense to use the profit generated instantly from sold goods (sales − variable costs = marginal profit) to cover the fixed costs that hit at month-end.

- Fixed Costs ÷ Marginal Profit Rate = Break-Even Point Sales

This is called CVP (Cost Volume Profit) analysis, calculating the sales volume at the point of "no profit, no loss." I’m not too confident in the above calculation, so please point out any mistakes.

This "how much do we need to sell to recover fixed costs" discussion isn’t directly tied to system implementation work, so it’s an area system vendors might overlook. However, for system users investing from Japan into Indonesia, conducting production and sales activities, and struggling to recover their investment quickly, it’s a critical issue.

System vendors tend to focus solely on system development and implementation, but if they can’t imagine the true purpose for the users, it becomes theoretical desk-bound nonsense.

Even if it’s hot, even if traffic jams cause back pain, or even if a rear-end collision leaves you inconvenienced for 10 days, visiting the field is what matters.

Increasing Direct Labor Time Ratio to Boost Productivity and Operating Profit

We continued running the boutique in a Bali shopping mall for about two years.

With annual tenant rent around 100 juta and a six-person SPG team (800,000 rupiah/month each), the monthly fixed costs came to 14 juta. Somehow, we managed to break even.

- Total Cost = Total Variable Costs + Total Fixed Costs

- Unit Price = Variable Unit Cost + Fixed Unit Cost

The variable unit cost (clothing purchase price) remains constant regardless of sales, while the fixed unit cost (tenant rent + SPG salaries) decreases inversely with sales volume.

When buying at 6 and selling at 10, the marginal profit rate is 0.4 (60% of the selling price). So, how much do we need to sell to recover the 14 juta/month fixed costs?

- 14 juta ÷ 0.4 = 35 juta/month in sales

After the Bali bombings centered in Jakarta reduced tourists to Bali, fixed costs (selling and administrative expenses) became a burden. After much deliberation, we relocated to Hardy’s temporarily on Danau Tamblingan Street in Sanur.

As a result, we reduced SPGs to two, tenant rent dropped to about 50 juta/year, and fixed costs were cut to 6 juta/month.

- 6 juta ÷ 0.4 = 15 juta/month in sales

However, Sanur back then was so quiet you could hear crickets, and despite the drastically lowered break-even point after the move, we barely managed to break even—a sad situation (tears).

So, I came up with a plan: use affordable turquoise, amethyst, and tiger’s eye natural stones, string them with silver beads to add value, and sell them at a higher profit margin.

I melted down leftover silver inventory for Japan that had been sitting at home, reworked it into beads, and strung them with fishing line into necklaces and bracelets for display. Western aunties bought them like crazy, and we started making decent profits.

Here’s the key point: by having idle SPGs make accessories like it was piecework, their salaries—previously 100% booked as selling and administrative expenses for promotional work—became direct labor costs due to the production time.

This was equivalent to:

- Producing in-house to lower purchase costs and increase marginal profit

- Converting selling and administrative expenses into direct labor costs for in-house production, saving outsourcing costs and boosting both gross and operating profit

In other words, "turning indirect labor time into direct labor time converts fixed costs into variable costs (purchase costs)."

- Marginal Profit (Gross Profit) = Sales − Variable Costs

SPGs producing at a lower wage rate than outsourced processing fees reduced variable costs.

- Operating Profit = Marginal Profit − Fixed Costs

With the same working hours and cost (salary), increasing the direct labor time ratio boosted output and operating profit despite the same hourly wage rate.

Managers Want to See Operating Profit by Department and Product

I ran my own business in Bali for about seven years, and the metrics I cared about daily were sales, cost of sales, and selling/administrative expenses—specifically, how much operating profit each product (or service) generated.

Managers inevitably want to see operating profit by department or product group, factoring in selling/administrative expenses. Unless there’s a mistake in manufacturing cost calculation leading to a loss, gross profit, which should naturally be positive, isn’t a direct management metric.

However, when I returned to Jakarta and became a system implementation field worker, I tended to think of business systems functionally, deductively viewing the flow from procurement and production to inventory and accounting.

In reality, Japanese company managers inductively trace from sales performance to inventory and procurement, needing breakdowns like departments or product groups.

How you categorize items in a business system’s item master depends on whether you prioritize inventory management convenience from a department manager’s perspective or sales connectivity from a salesperson’s or manager’s viewpoint.

The department master is based on the company’s organizational chart, but if you want finer profit-and-loss management by section, you need to define departments more granularly.

Conversely, you also need a common department to aggregate costs that can’t be split by department. First, define system departments flatly as cost centers, then define higher-level consolidated departments for report output units.

When leveraging a business system from a management perspective, you must design the master data to aggregate accumulated data by necessary breakdowns and include them in transaction input fields.

From Cost Center to Profit Center

When accumulating costs by work center, cost centers are often departments. Since only costs are aggregated without revenue, even highly profitable tasks or jobs with large costs tend to be avoided.

Thus, turning cost centers into profit centers—holding them accountable for both revenue and costs (profit and loss)—optimizes departments to maximize profit, though partial optimization doesn’t always lead to overall optimization.