Recording month-end inventory discrepancies as spoilage costs and including them in manufacturing costs reduces gross profit. Recording them as inventory shrinkage costs in cost of goods sold (COGS) also reduces gross profit, while recording them as extraordinary losses under non-operating expenses reduces operating profit. Accounting System in Indonesia The cloudification of accounting systems is advancing in Indonesia, with the three major local cloud systemsAccurate, Zahir, and Jurnalleading the market. However, in reality, it is said that fewer than 8% of domestic companies have implemented accounting systems. This is why new cloud-based accounting systems continue to be launched in what might seem like an already saturated Indonesian market. It suggests that both domestic and international IT startups see significant potential for cloud accounting systems to expand their market share locally. In Indonesia, automated journal entries due to the widespread use of accounting systems have become commonplace, and over the ... 続きを見る

Difference Between Physical Inventory Quantity and Theoretical Value

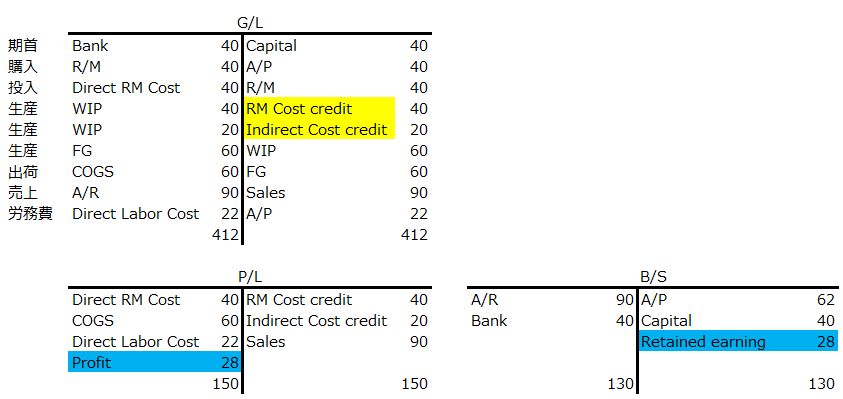

In a system using the perpetual method, where inventory receipts and issues generate accounting entries, the inventory asset account is increased when purchasing materials or parts, or when recording work-in-progress (WIP) or finished goods (F/G) output, and decreased when issuing materials or WIP, or shipping products.

- (Debit) Materials 40 (Credit) A/P 40

In this case, the inventory valuation amount and the accounting inventory asset balance are synchronized in real-time, allowing interim profit and loss statements (P/L) and balance sheets (B/S) to be viewed mid-month.

In such systems, material cost unit prices are typically updated in real-time using the moving average method, while other processing costs are assigned standard unit prices in the bill of materials (BOM).

Here, by recording material costs as a negative expense in a contra account (e.g., R/M Cost Credit) when issuing materials, the direct material cost account balance isn’t offset, enabling the breakdown of manufacturing costs to be detailed on the P/L.

- (Debit) Direct Material Costs 40 (Credit) Materials 40

- (Debit) WIP (Direct Material Cost Portion) 40 (Credit) R/M Cost Credit 40

When recording finished goods output, the processing cost portion is calculated by accumulating standard unit prices from the BOM and temporarily recorded as a negative expense in a contra account (e.g., Indirect Cost Credit), allowing the processing cost breakdown to be detailed as part of manufacturing costs on the P/L.

- (Debit) WIP (Processing Cost Portion) 20 (Credit) Indirect Cost Credit 20

- (Debit) F/G 60 (Credit) WIP (Direct Material Cost Portion + Processing Cost Portion) 60

Ultimately, the products are shipped and become COGS.

- (Debit) COGS 60 (Credit) F/G 60

- (Debit) A/R 90 (Credit) Sales 90

Since COGS includes processing costs, adjustments are made when the actual processing cost amount is finalized.

The method of recording the difference between WIP output and material input amounts as processing costs is called predetermined allocation in actual cost accounting, aimed at speeding up accounting. However, if actual input data is incorrect, it disrupts not only inventory quantities but also accounting figures.

Typically, errors in actual input are discovered during physical inventory counts. The correct response is to adjust mid-month production records retroactively after completing the month-end inventory, but often, the incorrectly recorded production lot has already been consumed in subsequent processes. For products with short lead times, they may already be shipped and invoiced.

Thus, you’re forced to cancel downstream invoices and shipping records in reverse order. However, in most systems, canceling shipments or invoices generates new invoice or shipping document numbers, which can affect document management for customers or vendors, making such corrections impractical.

Impact on Accounting When Adjusting Inventory Discrepancies in Inventory Management

In this case, adjusting inventory discrepancies through inventory management triggers automatic journal entries in the accounting system. If the physical inventory quantity is less than the theoretical value, the difference must either be expensed or capitalized.

If this discrepancy stems from an omission of NG (non-good) input, it should be recorded as spoilage costs and included in manufacturing costs, reducing the original gross profit (gross margin) below its actual value.

- COGS = Beginning Inventory + (Current Month Manufacturing Costs + Difference) – Ending Inventory

- Gross Profit = Sales – COGS

When recorded as inventory shrinkage costs in COGS during month-end adjustments:

- COGS = Beginning Inventory + Current Month Manufacturing Costs – (Ending Inventory – Difference)

- Gross Profit = Sales – COGS

When recorded as extraordinary losses under non-operating expenses:

- COGS = Beginning Inventory + Current Month Manufacturing Costs – Ending Inventory

- Gross Profit = Sales – COGS

- Operating Profit = Gross Profit – Difference

Ultimately, recording it anywhere results in some form of cost recognition, compressing profit. This doesn’t typically lead to debates like “Isn’t a system where production receipts and issues directly tie to accounting misaligned with the company’s actual revenue structure?”

The real issue to address is “the fact that deliveries to customers proceed without issue despite underreported actual input.” Factors causing discrepancies—such as unrecorded production via red slips or recording only good units despite significant defects—should be investigated to improve actual input processes starting the next month.

Systemization Isn’t Always the Right Answer

For implementing business systems in Indonesian factories, the most practical approach is to manage only quantities in production management receipts and issues, calculate inventory valuation amounts in batches after month-end inventory adjustments, and compute manufacturing costs and COGS using the three-way method.

This requires the following data interfaces between production management, cost management, and accounting:

- Interface production management system’s A/R and A/P to accounting.

- Interface accounting system’s fixed costs to the cost management system.

- Interface cost management system’s calculation results as journal entries to the accounting system.

However, these interfaces don’t necessarily need to be systemized; manual processes or double-entry are viable options.

Even with a systemized interface, the human task of “sequentially checking and correcting data from upstream to downstream” remains unchanged. In fact, systemization can create inconveniences like “downstream checks can’t start because upstream preparation isn’t ready.”

Accounting undeniably benefits from systemization for improved efficiency, but production management doesn’t always see efficiency gains from it. It’s a “game over if you say that” moment for system workers, but this feeling is especially strong in Indonesia.

A past system introduced with good intentions—directly linking inventory receipts/issues to accounting—can be manualized as follows, likely as a countermeasure when systemization complicates processes and humans can’t trace the basis of output figures:

Manage purchased materials with the system’s moving average unit price as usual:

- (Debit) R/M (Credit) A/P

Manage material issuance quantities in Excel:

No journal entries

Manage WIP production quantities in Excel:

No journal entries

Record product output in the system and manage product inventory valuation with the system’s standard unit price:

- (Debit) F/G (Credit) COGS

Deduct material quantities and amounts from the system based on physical inventory using the system’s moving average unit price:

- (Debit) COGS (Credit) R/M

Finalize WIP inventory valuation based on physical inventory using Excel’s standard unit price and generate accounting entries:

- (Debit) WIP (Credit) COGS

U.S. President Nixon proposed “honorable withdrawal” as a slogan to end the Vietnam War, which gained support from frontline troops and public opinion weary of the prolonged conflict.

If a system meant to simplify work exhausts on-site operators, “manualizing the system” might, in some cases, boost morale and improve efficiency.